【学者观点】中国在缅甸的大型项目:下一步呢?(中英文)

【学者观点】中国在缅甸的大型项目:下一步呢?

祝湘辉 云南大学缅甸研究院 10月21日

执行摘要

•中国在缅甸的投资在2010-2011财政年度达到顶峰,在随后的两年中急剧下降。

•中国加强了对ODI的监管,并坚持进行更严格的风险评估。同时,其国有企业承受着适应缅甸新的政治环境的压力,并对其投资行为做出了明显的改变。

•由民主联盟领导的政府于2016年上台,已与中国达成协议,在中缅经济走廊下引入2.0版的大型项目。

•部分由于缅甸对国家安全的担忧,部分由于缅甸即将举行的2020年大选,中国在实施其大型项目时表现出更多的谨慎和审慎态度。

介绍

鉴于缅甸在地理位置上接近中国,并且随着中国开始实行“走出去”政策,缅甸对中国地缘政治的重要性最近已大大提高。到军政府时代结束时,中国已经成为缅甸最重要的投资国之一。这导致人们越来越担心这些投资的性质。自2011年以来,缅甸自上而下的转型给中国在缅甸的投资带来了严重担忧。在由民主联盟领导的政府于2016年掌权后,中国的投资进展缓慢。

本文旨在解决两个关键问题:中国在缅甸的对外直接投资(ODI)背后的动机是什么?中国在缅甸的大型项目的前景如何?

转折点

中国在缅甸的ODI存量在2010-2011财年达到顶峰,达到140.6亿美元,约占缅甸批准的外国投资的70%。12011年缅甸的剧烈政治过渡标志着中国ODI进入缅甸的转折点。缅甸随着U Thein Sein政府给予新闻界更多自由并开展全面改革而经历了深刻的变革,而中国在缅甸的大型项目遭受了挫折。2自2011年Myitsone项目中止后,中国大幅缩减了规模缅甸的对外直接投资3

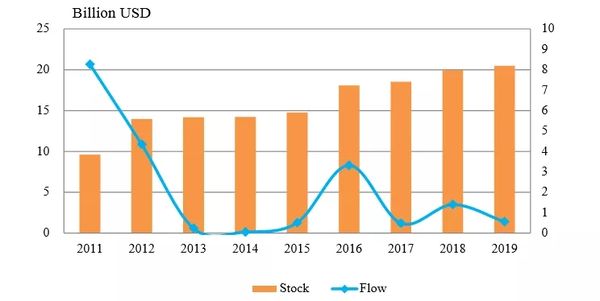

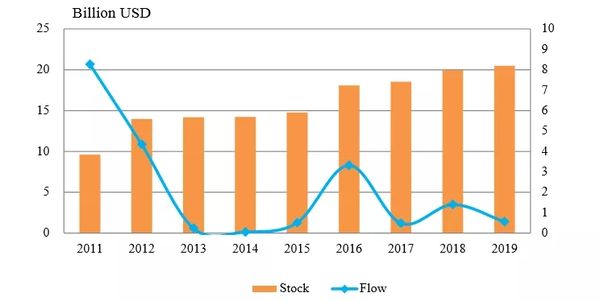

图表1:中国对缅甸的对外直接投资流量和存量(2011-2019)

资料来源:缅甸投资与公司管理局(DICA)数据

可以从图表1中看到中国对缅甸的ODI流入量和存量。2011年,中国对缅甸的ODI流入量达到85.6亿美元(用虚线表示),是历史最高水平。2012年,该额度急剧下降,与前一年相比大幅下降了52%。42013年,额度继续下降至2.3亿美元,在未来两年保持较低水平。2015年,该数字有所改善,达到5.1亿美元。然后,在2016年有了显着改善,显示出与前三年不一致的转变。2017年,这一界限再次下降,并在2018年和2019年保持在20亿美元以下。因此,从2011年到2018年,这些剧烈的波动恰逢缅甸的政治过渡。这强烈表明中国的对外直接投资与缅甸的国内政治之间存在关联。

中国对外直接投资流量的变化表明,中国在2011年之后改变了对缅甸的投资政策。图表显示,中国在那段时期已经意识到了巨大的风险,因此决定调整缅甸的投资规模并扭转其先前的大型项目模式。

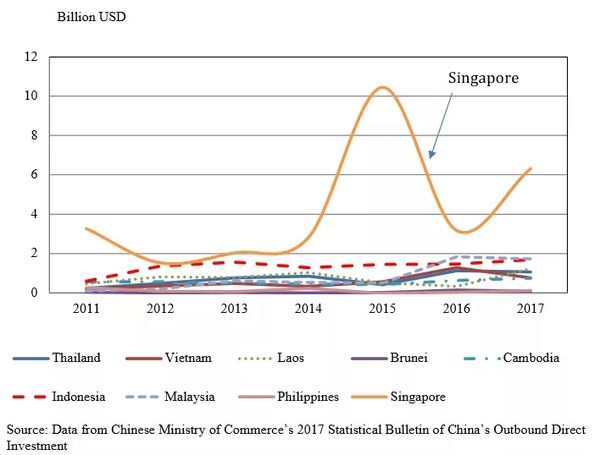

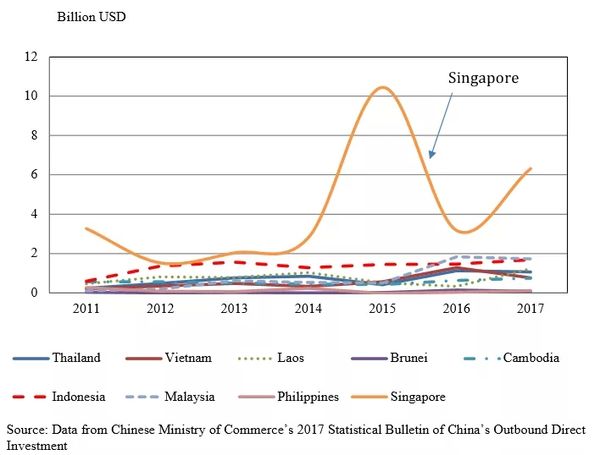

如下图所示,缅甸是东盟成员国中的一个特例,有关中国向其他东盟国家的ODI流入量(见图2)。

图2:中国对外直接投资流入其他东盟国家

图2显示,2011年至2017年,中国的ODI流入其他9个东盟国家。除新加坡有明显的高点和低点外,中国流入其他东盟国家的ODI相对稳定,没有剧烈波动。通过将9个东盟成员国和缅甸的数字相加,中国在2011年流入东南亚的ODI总额为214.6亿美元。在2017年激增至890.1亿美元。5在这7年期间,中国将其对东南亚的ODI增加了超过四倍。东盟每个国家的ODI存量也有所增加,尽管程度不同,这表明中国在东南亚具有很强的长期经济利益。

因此,图1中缅甸的ODI急剧波动与图2中除新加坡以外的大多数东盟国家不符。中国对缅甸的ODI流入从未在2011年恢复到最高峰。这表明中国政府在2016年对ODI的审查比对2011年的审查更为严格,并且它改变了对缅甸的经济政策。由于中国的大型项目遭受重大挫折,中国流入缅甸的ODI也有所下降。

中国大型项目的考察

有三个因素可以解释中国在缅甸的大型项目的存在。首先,中国不断增长的劳动力成本和资本成本迫使中国公司走向全球。6其次,中国必须确保长期的自然资源供应,以满足不断增长的国内需求。第三,经过几十年的权力下放,中国的国有企业(SOE)现在享有相当程度的自主权,他们面临着实现自己的增长目标的压力,从而导致它们之间的激烈竞争。因此,中国有几个大型项目,尤其是在石油,天然气,水力发电和采矿领域,成为缅甸经济的主要国际参与者。由于在这些领域进行投资需要大量资金和一定的技术能力,

作为伊洛瓦底江上游七个级联大坝项目的一部分,中国电力投资集团公司(CPI)一直在推动建设6000兆瓦密密松大坝。2009年12月,CPI与缅甸电力部(1)签署了合资协议并开始建设。商定,缅甸政府将获得15%的份额和10%的免费电力,其余90%出口到中国市场8,这是基于缅甸市场无法消耗10%的发电量的计算得出的然后。如果缅甸要求更多,则可以灵活调整10:90的比例。9自2011年以来,针对密松大坝的公众抗议活动获得了动力。反密宗的情绪逐渐融合为有影响力的环保主义和民族主义运动,

Letpadaung铜矿项目位于缅甸西北部的实皆省南部。它的设计目的是年产10万吨铜,投资额为10.6亿美元。112012年3月,在开始施工仅三个月后,当地村民举行了大规模抗议活动,该项目因此而停顿。2012年11月,对抗迅速升级,缅甸政府派出警察清理现场,冲突爆发,近一百名僧侣受伤。2013年3月,昂山素季为首的调查委员会提交了该项目的最终报告。它建议在进行必要的改进后继续该项目。122014年3月,该项目恢复进行,但偶尔也遭到抗议。在2016年3月,

缅甸-中国的石油和天然气管道是缅甸最大的基础设施投资之一。14771公里的原油管道旨在每年将2200万吨石油从中东和非洲经缅甸运输到中国西南部的昆明。与原油管道平行的是793公里的天然气管道,每年输送120亿立方米的天然气。该项目的实际投资高达44亿美元,合同期限为30年,必须移交给缅甸政府。15管道建设于2010年6月开始,大约3年后完成。16在建设阶段,一些缅甸非政府组织发布了有关强迫移民,环境破坏和侵犯人权行为的报告。17但是,

经验教训和加强监督的措施

从这些挫折中,中国吸取了很多教训。首先,其大型项目应获得当地社区的社会同意。其次,舆论会对政治体制产生外部压力,迫使东道国政府改变对项目的决定。第三,中国的投资模式存在缺陷,需要纠正,因此必须改善项目和监督制度18。

2013年全年,中国政府颁布了一系列与ODI相关的法规和指南。特别是2014年,中国的对外直接投资政策发生了重大变化。根据国家发展和改革委员会(国家发改委)的《境外投资项目核准,备案管理办法》(第9号令),19以及修订后的《境外投资管理办法》。根据中国商务部的规定,中国的对外直接投资进入了“备案备案和审批补充”的时期。202016年,政府发起了一场打击“非理性”投资活动的运动。21国家发改委在此发布了两项重要法规2017年下半年。第一个是2017年12月的“私营企业海外投资行为守则”,22第二项是2017年12月的《企业境外投资管理办法》(第11号令)。232017年1月,国务院国有资产监督管理委员会发布了《监管办法》。中央企业海外投资管理”,以采取负面清单,完成后评估和问责制等做法。2017年8月,国务院发布了《关于进一步指导和规范境外投资方向的指导意见》。24中国政府因此加强了对缅甸及其他国家国有企业投资的监管。国务院国有资产监督管理委员会(SASAC)发布了《中央企业境外投资监督管理办法》,采取了负面清单,完成后评估和问责制等做法。2017年8月,国务院发布了《关于进一步指导和规范境外投资方向的指导意见》。24中国政府因此加强了对缅甸及其他国家国有企业投资的监管。国务院国有资产监督管理委员会(SASAC)发布了《中央企业境外投资监督管理办法》,采取了负面清单,完成后评估和问责制等做法。2017年8月,国务院发布了《关于进一步指导和规范境外投资方向的指导意见》。24中国政府因此加强了对缅甸及其他国家国有企业投资的监管。

中国国有企业适应

中国国有企业面临适应缅甸新政治环境的压力,这导致其投资行为发生了明显变化。他们对当地多个利益集团的批评作出反应,并遵守东道国政府实施的更为严格的法规和标准。25在一个案例研究中,中石油于2017年6月发布了其关于石油的社会责任的最新报告。和天然气管道。它同意每年向当地社区提供200万美元的援助,并将其工作人员的本地化比例从之前的50%迅速提高到75%。26中石油还建立了以天然气为电力的皎漂电厂27在接受采访时,总统吴登盛的前顾问U Sein Win Aung 他说,缅甸方面已经对中石油沿线的援助项目进行了调查,发现村民对项目及其援助行动表示欢迎,例如“为我们的村庄铺平了道路。” 我们关系很好,很亲切”。28

在另一种情况下,参与Letpadaung铜矿项目的万宝公司于2013年采取了改善措施,将万宝公司的股份从49%降低到30%,缅甸联合经济控股公司从51%降低到19%,并增加了缅甸政府51%的股份。29它进行了另一轮土地补偿,并承诺每年花费100万美元用于社区援助。30作为维奇·鲍曼(Vicky Bowman)(缅甸负责任商业中心的主任,该中心为在缅甸开展业务的公司提供建议缅甸)曾经评论道,(中国投资者)“了解情况正在发生变化,并且他们正在开始改变自己的做法。” 31缅甸已经“走过了反华情绪的顶峰”,一些中国公司现在正在努力做到这一点。与社区紧密合作32

轶事证据表明,中国企业的做法似乎已经改变,但真正的考验将在于他们是否始终如一地正确实施。迄今为止,观察员注意到,当地人的反馈抱怨援助项目的执行不一致。尽管如此,与过去相比,中国企业的行为有所改善。

中国的巨型项目2.0版

自2016年以来,由于两国之间的关系升温,中国和缅甸已同意引入2.0版本的大型项目,并摆脱了中国企业在缅甸遇到的较早困难。

2017年11月19日,中国外交部长王毅在内比都与缅甸国务委员昂山素季举行会议上,提议建设中缅经济走廊(CMEC)。双方于2018年9月9日在北京签署了一份政府间谅解备忘录,以建设CMEC,这一广阔视野涵盖了投资,运输,边境经济合作区和数字丝绸之路等12个关键领域.33

Kyaukphyu经济特区项目是CMEC的旗舰项目。2015年12月,中国国际信托投资公司(CITIC)财团中标了两个项目:深海港口和工业区,总金额为73亿美元。34在接下来的三年中,中信财团举行了更多的竞标。与缅甸政府进行了十几轮谈判和近100次非正式会谈。352018年7月上旬,缅甸计划和财政部长U Soe Win表示:“为避免陷入债务陷阱,缅甸试图缩小缅甸的债务规模。 “ Kyaukphyu经济特区”。362018年11月8日,Kyaukphyu经济特区深海港项目框架协议在内比都签署。该项目的规模已缩减至13亿美元,第一阶段有两个泊位,缅甸的份额提高到30%,其中15%由缅甸政府持有,它将出资代替资本,另外15%由政府指定实体(主要由缅甸私人公司组成的GDE)负担,这将出资本身。37中信也更加注重满足各种要求,而不是匆忙完成项目。2019年7月2日,针对Kyaukphyu深海港项目启动了环境和社会影响评估(ESIA)和地质勘查的前期工作.38 Kyauphyu深海港项目还需要三份协议(投资协议,股东协议和土地租赁协议)。并签署额外的特许权协议。同样,Kyauphyu工业区项目仍在等待签署投资协议,

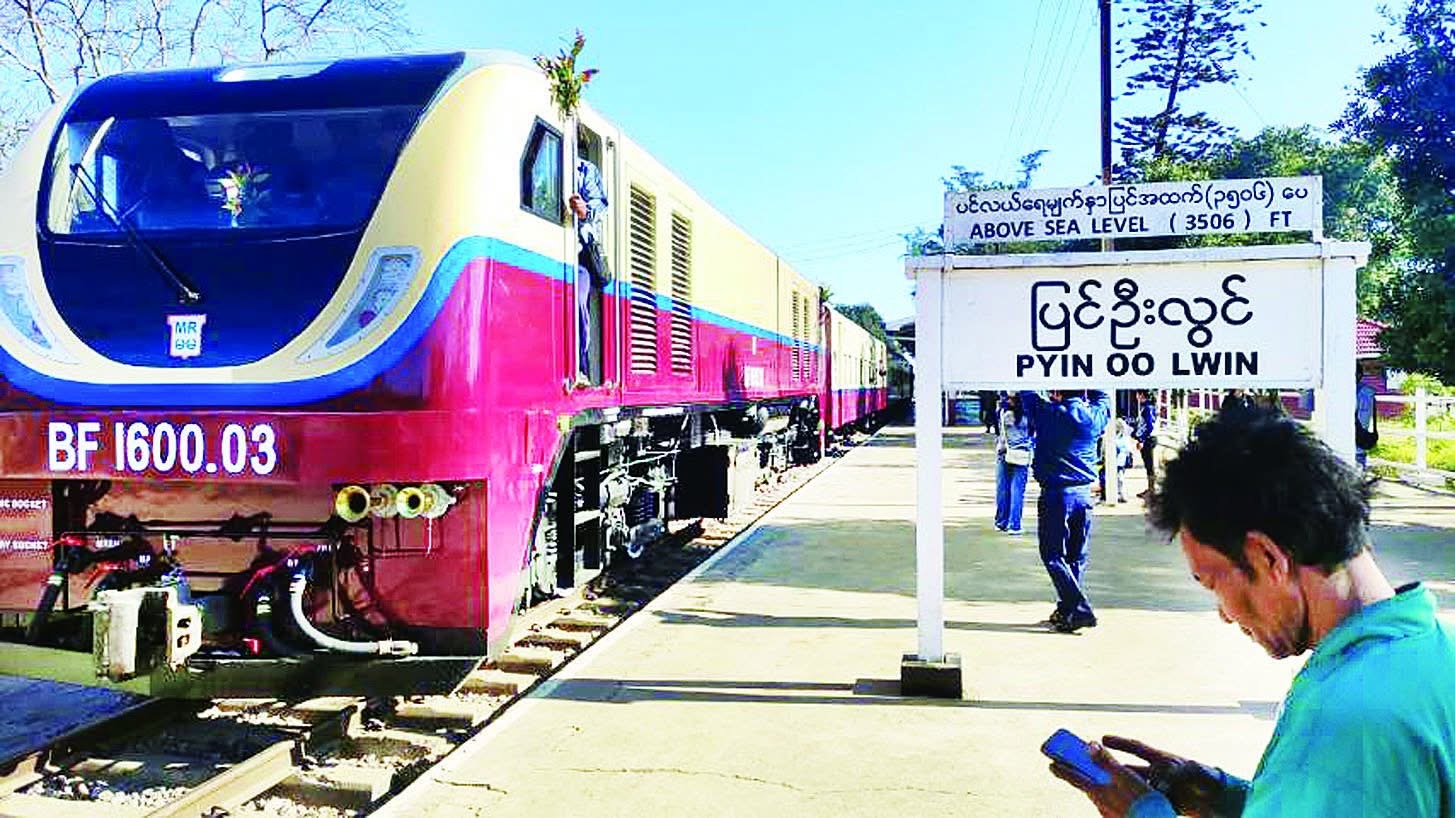

其他项目包括中缅铁路和跨境经济合作区。2018年10月,缅甸政府与中铁二院工程集团签署了关于铁路可行性研究的Muse-Mandalay谅解备忘录。完成后,这将连接曼德勒,内比都和仰光等主要城市,并推动仰光新城市项目的发展。

中国寻求促进瑞丽-缪斯,清水河-贡隆和后桥-坎帕蒂地区之间的跨境经济合作区以及曼德勒的Myotha和克钦邦的Myitkyina等经贸合作区的建设。瑞丽-缪斯跨境经济合作区最有前途。该区域的进出口总额占云南贸易的60%以上,占中国与缅甸贸易的30%。中国联通还交付了中国缅甸国际(CMI)地面电缆系统,该系统于2017年10月正式开始运营。该系统从中国的瑞丽延伸至缅甸的Ngwe Saung海滩,将缅甸与中国,

结论

中国在缅甸的大规模投资阶段已经结束。中国现在正集中精力为其项目寻求经济安全和降低风险。2011年密松大坝的停工表明,中国影响外国投资环境的能力是有限的,而且缅甸确实有能力抵制一个更大的国家,因为它感到自己的领土被遮盖了。缅甸不是一个无能为力的国家。41它的政府实际上知道如何在大国之间进行回旋。

尽管中国和缅甸官员经常谈论两国之间所谓的“ paukphaw”关系或“兄弟情谊”,但不断变化的动力迫使中国对缅甸采取更为谨慎的态度。中国采取了更为保守和低调的态度,这有助于解释为什么中国大幅减少了在缅甸的对外直接投资。

在与缅甸接触方面,中国受到经济考虑的驱动力大于出口其价值体系或追求任何军事或领土野心的愿望。对于缅甸而言,国家安全仍然是其最重要的问题,因此对中国的投资仍持怀疑态度。为了缓解这种担忧,中国国有企业已经开始通过开展公共关系活动,减轻环境和社会影响以及与更多的国际利益相关方合作来改变其行为方式。他们的投资不仅仅专注于资源开采和电力部门,而是将投资分散到更广泛的部门,包括制造,基础设施,连接性以及清洁能源,例如风能和太阳能。

随着2020年缅甸大选的临近,中国一定会密切关注结果,以显示其应如何进行未来的投资项目。政府的更迭或政策的转变可能对一个对大型项目的决策变得更加谨慎和审慎的中国来说,意味着更多的不确定性和风险。

【学者观点】China’s Mega-Projects in Myanmar: What Next?

祝湘辉 云南大学缅甸研究院 10月21日

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• China’s investments in Myanmar peaked in fiscal year 2010-2011 and declined sharply in the following two years.

• China has strengthened supervision over ODI and has insisted on more stringent risk assessments. At the same time, its SOEs are under pressure to adapt to Myanmar's new political climate, and have made noticeable changes to their investment behaviour.

• The NLD-led government that came to power in 2016 has agreed with China to introduce a version 2.0 of mega-projects under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

• Partly due to Myanmar’s concerns about national security, and partly due to Myanmar’s upcoming 2020 general election, China has shown more caution and prudence in implementing its mega-projects.

INTRODUCTION

Given Myanmar's geographical proximity to China, and with China embarking on its “going out” policy, Myanmar's importance to China’s geopolitics has risen significantly in recent times. By the end of the military junta-era, China had already become one of Myanmar's most crucial investors. This led to growing concern about the nature of these investments. Since 2011, the top-down transition in Myanmar posed severe concerns for China’s investments in Myanmar. After the NLD-led government took power in 2016, China’s investments has proceeded at a moderate pace.

This paper seeks to address two key questions: What are the motivations behind China's Outbound Direct Investment (ODI) in Myanmar and what are the prospects of China’s mega-projects in Myanmar?

A TURNING POINT

China’s ODI stock in Myanmar peaked in fiscal year 2010-2011 at US$14.06 billion and accounted for about 70% of Myanmar’s approved foreign investment.1 The drastic political transition in Myanmar in 2011 marked a turning point for China’s ODI into Myanmar. While Myanmar underwent a profound transformation with the U Thein Sein government granting more freedom for the press and launching all-round reform, Chinese mega-projects in Myanmar experienced setbacks.2 Following the suspension of the Myitsone project in 2011, China substantially scaled down its ODI in Myanmar.3

Chart 1: China's ODI Flows and Stocks into Myanmar (2011-2019)

Source: Data from Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA) of Myanmar

The flow into, and stock of China’s ODI in Myanmar can be illustrated using Chart 1. In 2011, Chinese ODI flow into Myanmar reached US$8.56 billion (denoted by the line), the highest in history. In 2012, this line fell sharply, registering a substantial dip of 52% compared to the year before.4 It continued to drop to US$230 million in 2013, to maintain a low base for the next two years. In 2015, it improved to reach US$510 million. Then, in 2016, a marked improvement, showing a shift inconsistent with the previous three years. In 2017, this line dropped again and stayed below US$2 billion in 2018 and 2019. From 2011 to 2018, therefore, these dramatic fluctuations coincided with Myanmar's political transition. This strongly suggests a correlation between China’s ODI and Myanmar domestic politics.

The shifts in China’s ODI flows suggests that China altered its investment policy towards Myanmar after 2011. The chart shows that China had perceived grave risks during that period and decided to adjust the investment size in Myanmar and reverse its previous megaproject model.

Myanmar is a distinctive case among ASEAN member-states as shown by the chart below on Chinese ODI flow into other ASEAN countries (see Chart 2).

Chart 2: Chinese ODI Flow into Other ASEAN Countries

Chart 2 shows China’s ODI flows into the other nine ASEAN countries from 2011 to 2017. With the exception of Singapore where there are obvious high points and low points, China’s ODI flows into the other ASEAN countries have been relatively stable, with no dramatic fluctuations. By adding up the nine ASEAN member-states and Myanmar’s figures, China’s total ODI flow into Southeast Asia stood at US$21.46 billion in 2011. It soared to US$89.01 billion in 2017.5 During this seven-year period, China increased its ODI to Southeast Asia by more than four times. The ODI stock in each ASEAN country has also increased, though at different levels, showing China’s strong long-term economic interest in Southeast Asia.

Therefore, Myanmar's dramatic ODI fluctuations in Chart 1 does not match most ASEAN countries in Chart 2 except Singapore. China’s ODI flow into Myanmar never regained its peak position in 2011. This indicates that the Chinese government scrutinized its ODI more strictly in 2016 than in 2011, and that it has changed its economic policy toward Myanmar. As China’s mega-projects experienced major setbacks, China’s ODI flow into Myanmar also declined.

VICISSITUDES OF CHINA’S MEGA-PROJECTS

There are three factors that can explain the presence of China’s mega-projects in Myanmar. First, rising labour costs and cost of capital in China are forcing Chinese companies to go global.6 Second, China must secure long-term supply of natural resources to meet rising domestic demand. Third, after decades of decentralization, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) now enjoy a considerable degree of autonomy, and they are under pressure to achieve their own growth targets, leading to intense competition among them. Thus, China became a major international player in Myanmar's economy, with the presence of several mega-projects, particularly in the oil, natural gas, hydropower and mining sectors. Since investing in these sectors require massive capital and a certain technological capability, most mega-projects are typically conducted by SOEs rather than private companies.7

As part of seven cascading dam projects on the upper reaches of the Irrawaddy River, China Power Investment Corporation (CPI) has been promoting the construction of the 6,000 MW Myitsone Dam. In December 2009, CPI and the Myanmar Ministry of Electric Power (1) signed a joint venture agreement and started construction. It was agreed that the Myanmar government would be provided with 15% share and 10% free electricity capacity, with the remaining 90% exported to the Chinese market,8 based on the calculation that the Myanmar market could not consume 10% of the electricity produced then. This ratio of 10:90 would be flexibly adjusted should Myanmar require more.9 Since 2011, public protests against the Myitsone dam gained impetus. Anti-Myitsone emotions gradually coalesced into an influential movement of environmentalism and nationalism, and the resulting pressure forced many government officials to change their attitudes toward the project.10 In September 2011, U Thein Sein surprised many observers by announcing the suspension of the Myitsone project.

The Letpadaung copper mine project is located in the south of Sagaing Region in northwestern Myanmar. It is designed to produce 100,000 tons of copper annually with an investment of US$1.06 billion.11 In March 2012, barely three months after the start of construction, local villagers staged large-scale protests, and the project ground to a halt. In November 2012, the antagonism quickly escalated, and when the Myanmar government dispatched police to clear the site, clashes broke out and nearly a hundred monks were injured. In March 2013, the Commission of Inquiry headed by Aung San Suu Kyi submitted a final report on the project. It recommended continuation of the project after some necessary improvements had been made.12 In March 2014, the project resumed, but amid occasional protests. In March 2016, the construction of the mine was completed and the production of cathode copper began.13

The Myanmar-China oil and gas pipelines are among the largest infrastructure investments in Myanmar.14 The 771-kilometer crude oil pipeline is designed to transport 22 million tons of oil yearly from the Middle East and Africa to Kunming in southwestern China via Myanmar. Running parallel to the crude oil pipeline is the 793-kilometer natural gas pipeline which transports 12 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year. The actual investment of the project is as high as US$4.4 billion with a contract period of 30 years before it has to be handed over to the Myanmar government.15 The pipelines construction began in June 2010 and were completed about 3 years later.16 During the construction phase, some Myanmar NGOs released reports that contained accusations of forced migration, environmental damage and human rights violations.17 However, compared to the Myitsone and the Letpadaung projects, the scope and intensity of criticism were limited.

LESSONS AND ENHANCEDSUPERVISION MEASURES

From these setbacks, China learned a number of lessons. First, its mega-projects should secure social consent from local communities. Second, public opinion can generate external pressure on the political establishment, forcing the host government to change its decisions on the projects. Third, China's investment model was flawed and needed correction, and it was imperative that the projects and the supervision regime improved.18

Throughout 2013, the Chinese government promulgated a series of regulations and guidelines related to ODI. In particular, 2014 witnessed a key change in China's ODI policy. With the promulgation of “The Administrative Measures for the Verification, Approval, and Record-Filing of Overseas Investment Projects” (Order No.9) by China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), 19 and the revised “Administrative Measures for Overseas Investment” by China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), China’s ODI entered a “record filing-based and approval-supplemented” period.20 In 2016, the government launched a campaign to fight “irrational” investment activities.21 NDRC issued two important regulations in late 2017. The first was “The Code of Conduct for the Overseas Investment by Private Enterprises” in December 2017,22 while the second was “The Administrative Measures for Overseas Investments by Enterprises” (Order No. 11) in December 2017.23 In January 2017, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) issued “Measures for the Supervision and Administration of Overseas Investments by Central Enterprises” in order to adopt practices such as negative list, after-completion evaluation and accountability. In August 2017, the State Council issued “The Guiding Opinion on Further Directing and Regulating at the Direction of Overseas Investments”.24 With these, the Chinese government tightened its supervision on SOE investments in Myanmar and other countries.

CHINESE SOES’ ADAPTATIONS

Chinese SOEs are under pressure to adapt to Myanmar's new political climate, and this has resulted in noticeable changes in their investment behaviour. They are reacting to criticism from multiple interest groups on the ground, and are abiding by the more stringent regulations and standards imposed by the host government.25 In one case study, CNPC in June 2017 issued an updated report on its social responsibility regarding the oil and gas pipelines. It agreed to provide US$2 million in assistance to the local community annually, and has further raised the localisation ratio of its working crew speedily to 75% from the previous 50%.26 CNPC also established the Kyaukpyu power plants, using natural gas for electricity generation for the locals.27 In an interview, U Sein Win Aung, former adviser to President U Thein Sein, said that the Myanmar side had conducted a survey of CNPC's assistance projects along the pipelines and found that the villagers embraced the project and its aid operations with remarks like “they paved the way for our village. We have a good relationship, very cordial”.28

In another case, the Wanbao company involved in the Letpadaung copper mine project introduced improvement measures in 2013 by reducing the Wanbao company share from 49% to 30%, and Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings from 51% to 19%, and adding an extra Myanmar government 51% share.29 It conducted another round of land compensation, and is committed to spending US$1 million each year for community assistance.30 As Vicky Bowman (director of the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, which offers advice to companies doing business in Myanmar) once commented, (Chinese investors) “understand that the situation is changing and they are starting to change their approaches”.31 Myanmar has “passed the peak” of anti-China sentiments, some Chinese companies are now trying to conform...and work closely with communities.32

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the approach of Chinese enterprises seems to have changed, but the real test will be on whether they practice it consistently and properly. Observers have so far noted feedback from locals complaining about inconsistency in the implementation of assistance projects. Nevertheless, compared to the past, the improvement in the actions of Chinese enterprises is worth noting.

CHINA'S MEGA-PROJECTS VERSION 2.0

China and Myanmar have agreed to introduce a version 2.0 of mega-projects due to warming relations between the two countries since 2016 and to move beyond the earlier difficulties encountered by Chinese enterprises in Myanmar.

On 19 November 2017, in his meeting in Naypyidaw with Myanmar State Councilor Aung San Suu Kyi, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi proposed the construction of the ChinaMyanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). On 9 September 2018, the two sides signed an intergovernmental MOU in Beijing to construct the CMEC, a broad vision encompassing 12 key fields such as investment, transport, border economic cooperation zones, and the digital silk road.33

The Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone project is a flagship component of the CMEC. In December 2015, the China International Trust Investment Corporation (CITIC) consortium won the bid for two projects: the deep-sea port and the industrial zone with a total amount ofUS$7.3 billion.34 In the following three years, the CITIC consortium held more than a dozen rounds of negotiations and nearly 100 informal talks with the Myanmar government.35 In early July 2018, Myanmar’s Minister of Planning and Finance U Soe Win said that to “avoid falling into the debt trap, Myanmar seeks to scale down the size of Kyaukphyu special economic zone”.36 On 8 November 2018, the Framework Agreement of Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone Deep Sea Port Project was signed in Naypyidaw. The scale of the project was reduced to US$1.3 billion with two berths in the first phase, and with Myanmar's share raised to 30%, of which 15% is held by the Myanmar government that will contribute land in lieu of capital, and another 15% borne by a Government Designated Entity (GDE comprising mostly Myanmar private companies) that will contribute capital per se.37 CITIC is also paying more attention to meeting various requirements rather than rush the project through in haste. On 2 July2019, preliminary works on Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) and geological survey for Kyaukphyu deep-sea port project were launched.38The Kyauphyu deep-sea port project requires three more agreements (investment agreements, shareholders agreements and land lease agreements) and an additional concession agreement to be signed. Likewise, the Kyauphyu industrial zone project is still awaiting the signing of the investment agreement, shareholders agreement and land lease agreement.39

Other projects include the China-Myanmar Railway and Cross-border Economic Cooperation Zones. In October 2018, the Myanmar government and China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group signed the Muse-Mandalay MOU on Railway Feasibility Study. When done, this will connect the key cities of Mandalay, Naypyidaw and Yangon and drive the development of Yangon's New City project.

China seeks to promote the construction of the Cross-border Economic Cooperation Zones between Ruili-Muse, Qingshuihe-Gunlong, and Houqiao-Kampaiti, as well as economic and trade cooperation zones such as Myotha in Mandalay and Myitkyina in Kachin State, among which the Ruili-Muse Cross-border Economic Cooperation Zone is the most promising. The total import and export volume of the zone accounts for more than 60% of Yunnan’s trade and 30% of China’s trade with Myanmar. China Unicom also delivered the China-Myanmar International (CMI) terrestrial cable system that officially commenced operations in October 2017. It runs from China’s Ruili to Myanmar's Ngwe Saung Beach, linking Myanmar to China, and can eventually be extended to Thailand and even Africa with the assistance of other AAE-1 cable systems currently under construction by several international parties.40

CONCLUSION

The phase of massive Chinese investment in Myanmar has ended. China is now focused on seeking economic security and risk reduction for its projects there. The 2011 suspension of the Myitsone Dam showed that China’s ability to influence the foreign investment climate is limited and that Myanmar does have the means to resist a larger country when it feels overshadowed in its own territory. Myanmar is not a powerless state.41 Its government actually knows how to manoeuver between big powers.

Though Chinese and Myanmar officials often talk about the so-called paukphaw relationship or “brotherhood” between the two nations, the changing dynamics have driven China to take a more cautious approach in Myanmar. China has adopted a more conservative and low-profile approach, and this helps explain why China has sharply reduced its ODI in Myanmar.

In engaging Myanmar, China has been driven more by economic considerations than by a wish to export its value system or pursue any military or territorial ambitions. For Myanmar, national security is still its paramount concern and therefore it remains skeptical of Chinese investments. To assuage such concerns, Chinese SOEs have begun to change the way they behave by conducting public relations activities, mitigating environmental and social impact, and working together with more international stakeholders. Instead of focusing solely on resource extraction and power sectors, their investments are diversifying to broader sectors, including manufacture, infrastructure, connectivity, and clean energy such as wind power and solar energy.

With Myanmar's 2020 general election approaching, China will certainly pay close attention to the outcome for signs of how it should proceed with future investment projects. Changes in government or shifts in policies may mean additional uncertainty and risk for a China that has become more careful and prudent concerning mega-project decisions.

评论列表 共有 0 条评论

最新导读

热门文章

发表评论 取消回复